Soy Field Brazil ©Alex Rodrigo Brondani

How can we achieve sustainability in commodity supply chains? Most stakeholders understand that supply chains are extremely intricate and convoluted, and once you start looking into that complexity, it appears overwhelming: there’s just so much that looks impossible to control. That’s why many sustainable agricultural commodities programmes try to find one, big, influential element and drive change there. Unfortunately, that can’t work, because it doesn’t account for the inter-dependencies, feedback loops, and myriad influences and consequences that make up supply chain ecosystems .

Important work has been done by many actors – often working independently or with limited partners – to optimise supply chain management, but without effective legal and policy frameworks to support improved supply chain management, conditions remain for deforestation within commodity supply chains. Transformation requires different types of interventions across multiple levels, sectors, and issues simultaneously, addressing supply systems, not just supply chains. That’s what the Good Growth Partnership (GGP)[1] and our Integrated Approach have been doing.

Brazil leads the world with over a third of all soy production[2]. Tracing the sustainability of land-use change for commodities production can be confusing, because conversion for soy often starts in the beef supply chain, when forest is cleared for pastureland – for which lower sustainability standards may apply – before being converted to soy production. Soy is also used as feed for livestock and aquaculture, so interventions to promote sustainable production of both commodities needs to be mutually supportive across many supply chains. The international market also has a powerful influence on policies and practices at many levels, and the price of soy futures in summer 2022 have been close to an all-time high[3]. Since higher agricultural commodity prices are directly correlated with higher deforestation[4], these factors will impact the attractiveness of land to investors, incentives to convert land use, and the willingness of actors throughout the soy supply chain to move towards more sustainable long-term practices and away from intensive or exploitative agricultural practices that promise significant financial short-term returns. These variables and influences are also at work in palm oil production, with palm oil futures prices in summer 2022 at an all-time high.

_______________

[1] Working across production, financing and demand, the Good Growth Partnership (GGP) convenes a wide range of stakeholders and initiatives to reduce deforestation and enable sustainable development. In its pilot phase (2017-2022), the GGP was funded by the Global Environment Facility, led by the United Nations Development Programme and implemented in collaboration with Conservation International, the International Finance Corporation, UN Environment and World Wildlife Fund. It focused on three global commodity supply chains – soy, beef and palm oil – and four countries associated with them – Brazil, Paraguay, Indonesia and Liberia.

[2] https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Oilseeds%20and%20Products%20Annual_Brasilia_Brazil_BR2022-0026

[3] https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/soybeans

[4] Harding, T., J. Herzberg, and K. Kuralbayeva. 2021. “Commodity prices and robust environmental regulation: Evidence from deforestation in Brazil.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 108 (2021) 102452. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102452

Soy Plant Brazil © Getty Images

These influences at the global level create significant difficulties in strengthening and implementing laws to protect vulnerable ecosystems, which is why the GGP has been working not only at the landscape level with producers, but with national and global finance and companies too – and in private-public sector collaboration – to build awareness of the importance of ecologically sustainable decision making, for tangible reasons that speak directly to the key performance indicators of the private sector. GGP training and advocacy are helping international corporations and investors understand how to set precise commitments to deforestation-free and conversion-free supply chains, which are workable and can be monitored, and we have helped develop guidelines on identifying and offering deforestation- and conversion-free investment opportunities to investors. We have also been helping decision makers in the supply chain – including the banks, financial institutions, and investors which finance them – better understand their supply chains, so they can see the link between their decisions and ecosystem degradation, and improve their traceability. (For more information see Trase Insights and IFC’s support to COFCO.) We have also been working with national banks and financial institutions, including the Brazil Central Bank, to define and implement risk management strategies for ecologically unsustainable investments.

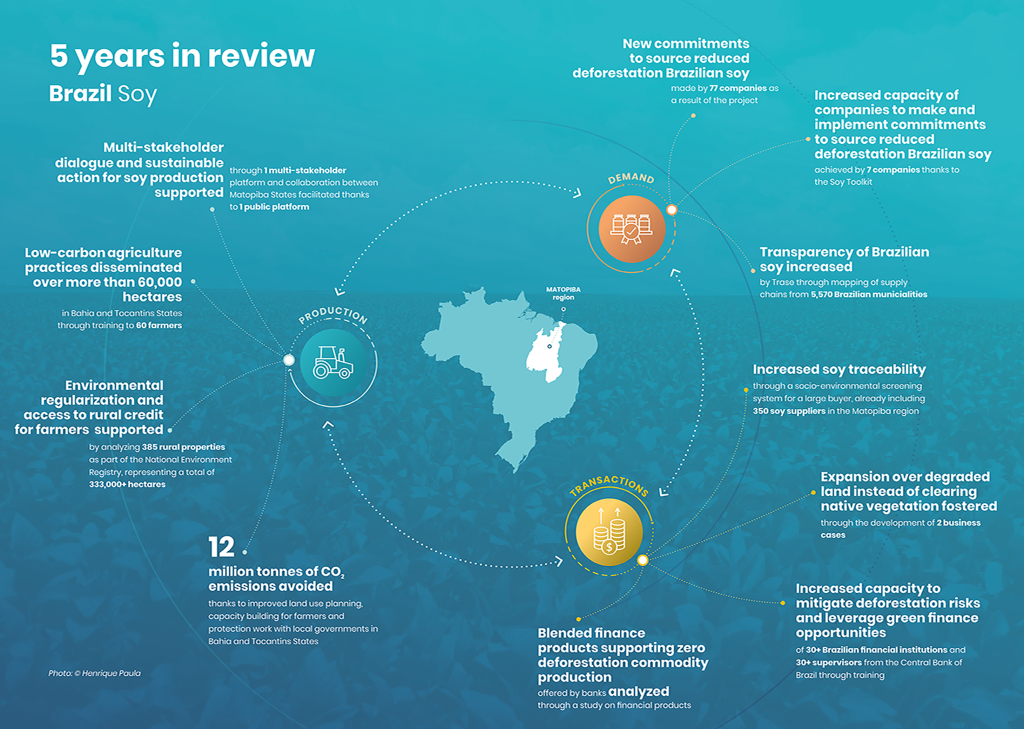

Understanding of sustainability in soy markets brings additional complexities. Soy is something of an ‘invisible’ commodity, because it is mostly used not to produce tofu burgers, but to produce actual burgers, as well as fish, chicken, and pork. For that reason, while certification is a useful tool, end-consumer demand for sustainable soy is limited compared to more visible like beef. Awareness of sustainability also varies from market to market.Responding to that variance, the GGP worked with NGO partner Proforest to develop a Soy Toolkit in English, Mandarin, Portuguese and Spanish. The toolkit gives tangible information and training to help companies integrate sustainability into their sourcing strategies, conduct risk analysis, establish purchase control systems, and monitor, verify, and report on progress. The GGP has also directly engaged with companies to encourage and help them in defining commitments for sourcing reduced-deforestation Brazilian soy, sending clear market signals to Brazilian traders. More information about concrete results from the GGP’s activities can be found here.

Nebulous perceptions about sustainability – and of unintended effects and feedback loops – also lurk in the zone of regulations, agricultural and land-use practices, and transactions. Soy produced in Brazil and exported around the world for animal feed, is influenced by a wide range of international policies and commitments, Brazilian and consumer country regulations, and voluntary standards and requirements of financial institutions and private sector initiatives. However continuous efforts to raise awareness of sustainability in the sector both locally and internationally, through the GGP and other public and private actors, have improved the reputation of soy produced in the Amazon, laying the groundwork for further developments in policy, planning, and practice more widely.

Governance mechanisms such as environmental laws and inclusive and participatory land use planning supported by effective land registration are essential tools to enable reduced deforestation. Brazil´s sophisticated Forest Code limits the expansion of production in Permanent Preservation Areas (Áreas de Preservação Permanente – APP) and Legal Forest Reserves, and creates incentives for rural producers to invest in technologies that modernize agriculture and in practices conducive to productivity gains. To access incentives, producers need to register their properties in the Rural Environmental Registry (Cadastro Ambiental Rural – CAR), and states need to validate these entries. Unfortunately most states are lagging behind, making it difficult for Brazil to harness the power of its sophisticated environmental law. To address this issue, the GGP supported target states in the MATOPIBA region with CAR validation, and helped strengthen the environmental protection of 1,158,000 hectares in Conservation Areas in the States of Bahia and Tocantins. Combined with the promotion of low-carbon agricultural and sustainable intensification practices in cattle and soy farms, under the ABC Plan federal policy, these joint interventions allow the protection of important biodiversity areas, while encouraging more sustainable practices on already cultivated or degraded land.

The system mapping exercises of the soy supply chain in Brazil, and the beef supply chain in Paraguay, (see here and here) showed how many interdependencies, feedback loops, and unexpected outcomes there are. Incentives, disincentives, and rationales need to be reinforced throughout the multiple layers in a system, to create meaningful, lasting change, and this can play out in diverse ways. For example, understanding of the value of sustainable farming can be undermined by disinterested downstream sourcing companies. Alternatively, both ends of the supply chain might be committed to sustainability, but the legal frameworks may support intensive, extractive agricultural practice, and local fiscal structures can place a higher value on land conversion and speculation than on healthy forest ecosystems. Or legal frameworks might be in place to push production away from important ecosystems, but maybe there’s no financing for producers to invest in sustainable intensification practices, or to restore degraded land into productive use for expansion.

On the topic of using degraded land, in 2017 over 60 Brazilian and international NGOs, foundations, and scientific institutes called in the ‘Cerrado Manifesto’ for greater awareness and activation of support for the transformation of attitudes, responsibility, and practices. The GGP has been working hard to further disseminate and respond to this call with advocacy, training, and advisory work at all levels. Building a business case for rehabilitation of degraded land in the Cerrado in order to encourage farmers and companies to expand soy cultivation over degraded land instead of clearing native vegetation has been a key achievement of the GGP, raising awareness of these practices with soy farmers, traders, and financial institutions. Innovative green financing mechanisms and understanding of the need for sustainability in investment decisions are making progress but are nascent. Alignment of international sustainability criteria is still waiting in the wings. The GGP now needs donor support to continue with this and our other many activities, helping to establish financial incentives to grow soy on land that is already cleared rather than converting forest, and the regulatory changes to support it.

The GGP has been proud to foster collective action at local, national, and global level towards a more sustainable future for agricultural commodities supply chains. However, the road to sustainable soy is long. As lessons from the GGP show, more needs to be done in an integrated fashion across the policy and incentive levers of systemic change at various geographic scales. We look forward to continuing this journey. Please consider joining us!